A captivating question has long intrigued historians and archaeologists: why did some ancient cities last for centuries or even millennia, while others vanished rapidly or were forgotten over time? To solve this riddle, a team of researchers from the United States conducted a comprehensive and innovative study, recently published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution , in which they examined 24 ancient Mesoamerican cities searching for answers to this mystery.

The study findings showed that the Mesoamerican cities that endured the longest had certain features in common. These included collective governing practices, high levels of cooperation and coordination between families, and substantial investments in infrastructure projects. These elements were essential in ancient Americas, where numerous natural disasters and other catastrophes constantly threatened the survival of cities and their vulnerable populations.

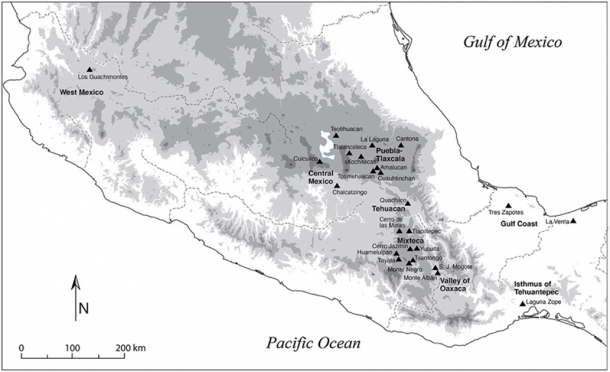

Map depicting the location of the 24 ancient Mesoamerican cities included in the study. (Feinman, G. et. al / CC BY 4.0 )

The Death and Life of Great Mesoamerican Cities

Mesoamerican cities have been the focus of a long-term study conducted by lead author Gary Feinman, the MacArthur Curator of Anthropology at the Field Museum of Chicago, and his colleagues. They have examined urban areas in Mesoamerica that date back to antiquity. Through their research, they have determined that democratic governing structures played a significant role in the endurance of these cities for centuries.

On the other hand, authoritarian regimes in Mesoamerica faced difficulties sustaining their political structures and population centers in the long run. Despite their power and prosperity during their peak, these regimes failed to maintain their city-states over time. As a result, the study has shed light on the importance of democratic governing structures in the development and survival of Mesoamerican cities.

- The Greatest Discovery Never Made – Ancient Civilizations Thrived With NO Ruling Elite

- The Maya People Still Have So Much to Teach Us

In their new study, the researchers adopted a targeted approach, focusing their analysis on 24 cities founded between 1,000 and 300 BC. These cities were all situated in the western region of prehistoric Mesoamerica, which encompassed northern Central America and the southern two-thirds of Mexico. Prior to 1,000 BC, the people of Mesoamerica lived mostly in small villages. It wasn’t until later that cities with larger populations began to emerge.

In this project, the researchers weren’t relying on written records to guide them. Instead, they focused on the characteristics of ancient ruins discovered by archaeologists, which are plentiful in Mesoamerica and offer important clues about the social, economic and political practices of the culture that built ancient urban settlements. “We looked at public architecture, we looked at the nature of the economy and what sustained the cities. We looked at the signs of rulership, whether they seem to be heavily personalized or not,” Feinman explained in a Field Museum press release .

Buildings on the west side of the large, open central plaza of Monte Alban, a city that lasted for 1,300 years. (WitR / Adobe Stock)

Democracy and Autocracy in the Architecture of Mesoamerican Cities

In trying to reach conclusions about why some Mesoamerican cities endured for centuries, while others didn’t, the researchers studied the shapes, sizes, functions and distribution of buildings, plazas, monuments, infrastructure projects and more. They operated under the assumption that grand architectural projects celebrating individual rulers were signs of an autocratic and highly unequal society, while projects dedicated to groups of leaders or to simple citizens indicated more democratically distributed power sharing arrangements.

The archaeologists and anthropologists involved in the study, which included Feinman and David Carballo of Boston University, Linda Nicholas of the Field Museum, and Stephen Kowalewski of the University of Georgia, confirmed their earlier findings that collective forms of government were conducive to longer urban longevity.

But even among the cities that had democratic architecture and structures some cities lasted much longer than others, showing that additional factors must be involved. “We looked for evidence of path dependence, which basically means the actions or investments that people make that later end up constraining or fostering how they respond to subsequent hazards or challenges,” Feinman said.

Ruins of the hilltop settlement of Monte Negro in Oaxaca show that the infrastructure lacked a shared central space and its apogee only lasted about 200 years. (Lon&Queta / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

What Infrastructure Choices Reveal About Governance in Mesoamerican Cities

This approach inevitably led them to take a closer look at infrastructure choices in Mesoamerican cities. It also motivated them to investigate cooperative arrangements that might have linked various families or households more closely together. What they found is that Mesoamerican cities that constructed dense, interconnected residential spaces and incorporated expansive central plazas where people could gather in large numbers were more sustainable over the long term than cities that were more atomized or divided along class or economic lines.

The study concluded that Mesoamerican cities that linked people together like this were better prepared to survive the daunting environmental challenges and natural disasters that plagued the region in ancient times. Mesoamerican societies in the first millennium BC had to deal with droughts, hurricanes, flooding, earthquakes and crop failures, not to mention the ever-present threat of invasion by rival settlements and population groups.

In reference to the researchers’ discovery that governing systems played a vital role in sustainability, study co-author Linda Nicholas, an adjunct curator at the Field Museum, stated that “responses to crises and disasters are to a degree political.” The infrastructure choices such cities made reflected their egalitarian inclinations, and the cohesiveness and sense of shared purpose they fostered would have been maintained even during the harshest and hardest times.

Surviving Climate Change: Lessons from the Ancients

It’s likely that people felt more emotionally invested in their cities when they participated in the decision-making processes in one way or another, and also when they benefitted directly from their cities’ prosperity. This would have given them extra incentive to stay around in the wake of a disaster, doing their best to contribute to the process of reconstruction.

- Drought-Induced Conflict Caused Collapse of 15th Century Maya Capital

- Can Any Civilization Make It Through Climate Change?

The results of this study reveal important facts about how and why certain cities survived in the ancient world. But the researchers are certain their findings are also relevant to today. “You cannot evaluate responses to catastrophes like earthquakes, or threats like climatic change, without considering governance,” stressed Feinman, “The past is an incredible resource to understand how to address contemporary issues.”

As we face the challenges of climate change and natural disasters, we can take inspiration from the resilience of certain ancient Mesoamerican cities dating back 3,000 years. Though environmental catastrophes are inevitable, they do not have to mean the downfall of a civilization. By studying the governance structures and collective practices that allowed these cities to endure for centuries, we can learn valuable lessons and apply them to our own efforts to build sustainable and resilient communities.

Top image: Representational image of a fictional Mesoamerican city. Source: fergregory / Adobe Stock

By Nathan Falde