There have been a number of high-profile reconstructions of historical figures recently and it seems like whenever a reconstruction is shared there is controversy and argument about whether the person it portrays really looked like their facsimile. However controversial they can be, attempting to reconstruct the faces of our ancestors is a popular way of humanizing the past and engaging the general public.

It has always been seen as valuable in the forensic field as a way of helping to identify John and Jane Doe’s, but the technique has increased in popularity among archaeologists and historians thanks to shows like Meet the Ancestors and History Cold Case.

From Tutankhamun to Lucy the Australopithecus, reconstructions help us to realize that the people we read about in books really were people and perhaps empathize more with the way they lived. But how confident can we be that we really are seeing the person as they were in life?

Turkana Boy – Forensic facial reconstruction/approximation. (Drbogdan / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Recent Controversy

2018 brought us a number of controversial facial reconstructions. The University of Bristol’s reconstruction of Egyptian queen Nefertiti was accused of whitewashing, while a reconstruction of the so called “ Cheddar Man ” from Somerset in England caused an outcry over the decision to give him very dark skin.

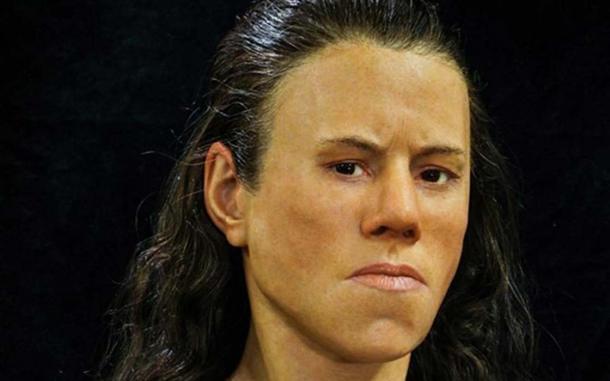

Meanwhile the reconstruction of a teenager nicknamed Avgi (‘Dawn’) who lived 9000 years ago in Ancient Greece, has been the subject of ridicule for different reasons as people have criticized the sculptor for giving her such a stern expression (though she would probably have looked quite sternly at the people teasing her for looking masculine!)

The face of the teenager ‘Avgi’ reconstructed from the 9000-year-old skull found in Greece. (Image: Oscar Nilsson )

Art or Science?

Bringing people back to life through reconstructions takes a mix of art and science, but it is not always easy to determine whether it is more art than science and it varies from case to case. Tackling the reconstruction of an anonymous woman like Avgi is a very different task to reconstructing a figure like Cleopatra who was described in detail by her contemporaries and survives in images such as coins with her profile on them.

Each of them presents their own challenges and needs for creative input.

There is an art in deciphering which elements of flattering portraits of Elizabeth I are accurate, so a realistic but recognizable animatronic head of the infamous monarch can be constructed. But there is also an art in imagining what a fashionable hairstyle may have been for a young woman in the European Bronze Age.

In both cases the image is built around the framework of facial features which are determined in a decidedly scientific way using osteometric data sets and precise measurements of the skull. Where pieces are missing, complex formulas are used to complete the skull so a reconstruction can be made.

- Facial Reconstruction Brings People Face-to-Face With Their Ancient Ancestors

- New research suggests Tutankhamun died from genetic weakness caused by family inbreeding

- Five Surprising Things DNA has Revealed About our Ancestors

Taung child – Facial forensic reconstruction. ( Cicero Moraes / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Unfortunately for the forensic artists who dedicate themselves to reconstructing people from the near and distant past, it is a skill which is criticized for its inaccuracy by both scientists and artists. Scientists argue that reconstructions are too subjective and are reliant on the artistic talent of the person undertaking them – the best forensic anthropologists in the world may not be great artists. Criticism from artists is that the field is too reliant on data sets and averages and will only ever produce a likeness which is of a similar facial type rather than managing to capture a characteristic likeness.

Recent Advances

Facial reconstructions may have been around since the Victorian era, but it has certainly changed over the years and the reproductions that are produced today have the advantages of modern technology and research to improve their accuracy. Digital reconstructions mean that it is now quick and easy to change things like hair style and eye color allowing a variety of possibilities to be presented and altered if research provides new evidence.

Furthermore, the controversial decision to give Cheddar Man dark skin was based on DNA evidence. Until recently it has not been possible to determine features this way and this breakthrough has taken away some of the inaccuracies and uncertainties from reproductions.

Hair and eye color have traditionally been open for interpretation and the 2016 reconstruction of a Bronze Age woman nicknamed Ava was given wavy blonde hair and blue eyes by the artist. Thanks to DNA analysis the reproduction was updated in 2018 to reflect evidence she had straight black hair and brown eyes.

Reconstruction of Myrtis, now DNA can tell us hair and eye color. (Materialscientist / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

But DNA analysis is an expensive process and it is not always possible to analyze the bones of the person that is being reconstructed, so it is likely that artistic license will remain an aspect of forensic reconstructions for the foreseeable future. This will inevitably cause debate about the accuracy of any reconstructions. But reconstructions continue to inspire and help people connect with the past, so even with their faults they are a trend that is here to stay.

Top image: Nefertiti Facial Reconstruction. Source: Shadesofheroin / CC BY-SA 4.0

References

CNN. 2018. Queen Nefertiti’s skin tone controversy. [Online] Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/videos/world/2018/02/12/queen-nefertiti-recreation-controversy-orig-tc.cnn

Daley, J. 2016. Meet Ava a Bronze Age Woman From the Scottish Highlands. [Online] Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/meet-ava-bronze-age-woman-scottish-highlands-180959988/

Daley, J. 2018. No, Wait, This Is the Real Ava, a Bronze Age Woman From the Scottish Highlands. [Online] Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/no-wait-real-ava-bronze-age-woman-scottish-highlands-180970950/

Devlin, H. 2018. First modern Britons had ‘dark to black’ skin, Cheddar Man DNA analysis reveals. [Online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/feb/07/first-modern-britons-dark-black-skin-cheddar-man-dna-analysis-reveals

Gibbens, S. 2018. Face of 9,000-year-old teenager reconstructed. [Online] Available at: https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/01/archaeology-agvi-greek-stoneage-facial-reconstruction/

John, D. 2018. Is this the real face of Elizabeth I?. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20181012-is-this-the-real-face-of-the-virgin-queen

Wilkinson, S. 2010. Facial reconstruction – anatomical art or artistic anatomy? [Online] Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2815945/